Have you ever heard people laugh as if birds were flying out of their mouths? Or thought about how alive objects can be? Everything seems possible in Ece Temelkuran’s latest novel Time of the Mute Swans (her own suggestion for the translation of Devir that she kindly provided me with). Told through the eyes of two children, Ayşe and Ali, this book first of all gives interesting insights into the turbulent times between 1971 and 1980 when two coups d’états took place in Turkey. Those who are not familiar with Turkish history, will learn a lot about this dark era by following the traces of the Bakar and Akgün families. In those times, the word “communist” was an insult; homes of the poor living in slums were burnt down; being against the government could mean being tortured by the police… Looking at today’s Turkey, some parallels can certainly be drawn. However, Ece Temelkuran does not only highlight the role of history in this novel, but also the role of personal memory, kept alive by old letters, photos and stories. After all, it is not without reason that we find the motto “The things that should not be forgotten remain. But what about the things we won’t remember?” on the book cover.

Without doubt, the leitmotif of mute swans and their broken wings needs to be analyzed in more detail. The little boy Ali is as mute as the swans he wants to save from Ankara’s Kuğulu Park (“Swan Park”) – an idea Ece Temelkuran got from similar actions at Gezi where children saved swans from gas bombs. The cruel action of breaking the wings of these white, innocent-looking birds appears to have a deeper symbolic meaning. In the historical context described by Ece Temelkuran, hindering the swans from flying away might stand for restricting the Turkish people’s freedom of expression. Being mute like swans that can no longer escape has become the fate of a whole population. This is an inhuman decade, taking away even the joys of childhood by confronting children (who are already suffering from a considerable lack of love) with death in its many forms.

Ali’s family lives in a slum where misery is not an exception but the rule. The boy only gets the chance to spend time at Ayşe’s rather wealthy home because his mother is the Bakars’ cleaning lady. He is obviously a traumatized child who rarely talks and often seems to be paralyzed. Most people regard him therefore as mentally retarded, although he is, in fact, highly sensitive and intelligent. Having listened to adult conversations and also witnessed scenes of violence, he and Ayşe have developed their own perception of reality. Even though their backgrounds are very different, they are strongly united by their pursuit of justice and their focus on the living. This might be one of the sources that gives these children the power to struggle for their ideals.

In Ali’s and Ayşe’s world, even particular smells or objects like strings, lighters, shoes or needles have their own life. Ali carries around all kinds of strings which in the course of the novel serve different purposes and thus are kept alive. He also has a list with all the things he would like to achieve before his death. Ayşe becomes his ally, filling the Turkish parliament with butterflies and eventually also saving a swan from the park in the middle of the night together with Ali. Both children believe that their last action will heal the “broken wings” of those who died for a better world. They want their swan to fly away – free like a paper kite of which Ali could only keep the cord he now puts on the swan’s leg. The innocent logic that guides all of Ayşe’s and Ali’s actions is deeply touching.

The structure of the book is extremely rich, playing with parallel scenes, narrator voices, metaphors and songs. Ece Temelkuran’s Devir is also a unique musical experience. Different melodies of laughter and a wide variety of songs accompany us through the whole novel. I found myself on a discovery trip through the history of Turkish music, listening to songs like “Şarap Mahzende Yıllanır” mentioned in the book – at times contrasting, at times underlining ongoing historical events:

In between chapters, we additionally learn a lot about fascist reactions to transsexual singers like Zeki Müren and Bülent Ersoy. And again there is the leitmotif of flying away and never coming back: “One way ticket to the moon” is one example of it; another is Ayşe’s statement that listening to music makes her feel her arms growing…

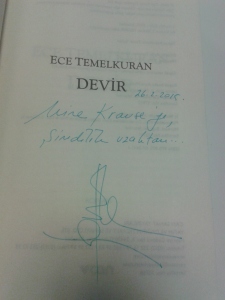

Ankara’s Kuğulu Park is certainly the best place to start this reading adventure. Thanks to a dear friend, I came into the possession of a signed copy of this wonderful novel at the right place at the right time. Those who know Turkey’s capital, will find themselves discovering this city with different eyes. While walking down Cinnah, going for a walk in Tunalı Hilmi and later sitting down in this cozy Swan Park, I somehow followed Ayşe and Ali around, going back with them in time, but also wondering how they would see Turkey today. Their belief in saving the world should give the young Turkish population some hope. Of course, such a positive vision is not only valid for Turkey: If we all learned to see swans through the innocent eyes of children and found it important to protect them, the world would probably be a more peaceful place.

Thank you, Ece Temelkuran, for reminding us how to fly…

Paris, 07/04/2015 © Mine Krause

Most interesting site, Mine! Will certainly return in search for more news about Turkish literature 🙂

Best and warmest wishes

Anders Dahlgren

Mediterranean Poetry